Introduction

We have already done quite a bit on improving our  Bible study techniques. In the first article we focused on understanding what it is we are reading, then next we looked at the books that make up our Bible and in the previous study we looked at how the different phrases in a verse move from the original context to our modern time. In this study we will now focus on the lowest level of Bible study, namely the words that make up the phrases. We so often hear the term “Word Study†being used but very few people that use this term have a full understanding of what it really means. I endeavor to show you with this article that word study is a lot more than simply looking up the original word of the manuscript and then finding a definition in your favorite lexicon. I will also call your attention to a couple of typical mistakes that we tend to make at the start and how you could avoid these.

Bible study techniques. In the first article we focused on understanding what it is we are reading, then next we looked at the books that make up our Bible and in the previous study we looked at how the different phrases in a verse move from the original context to our modern time. In this study we will now focus on the lowest level of Bible study, namely the words that make up the phrases. We so often hear the term “Word Study†being used but very few people that use this term have a full understanding of what it really means. I endeavor to show you with this article that word study is a lot more than simply looking up the original word of the manuscript and then finding a definition in your favorite lexicon. I will also call your attention to a couple of typical mistakes that we tend to make at the start and how you could avoid these.

I will provide you with information on the tools that you should use in your word studies and also the techniques that you could use. As I have stated in previous articles, I am not trying to tell you that this is the only way, it is simply the techniques that I have investigated and found of real use for myself.

Once again, the Bible is not just another book that we could apply our typical languages skills on, it is holy inspired Scripture. Therefor, you cannot do any Bible study without the Ruach (Spirit) of YHVH leading you. Please pray about these studies that you do to ensure that you will receive His truth.

Biblical languages

The Bible manuscripts we have today are written in three languages: Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek. These languages are not known by most of us today. Therefor we use a translation of the text in our preferred language. When we get down to the level of doing the study of the words, it is best that we use the original word in the manuscript as the basis of our investigation. If you study the use of a specific word in the Tanakh, it is best if you study the Hebrew word used in the manuscript. A person that has a good understanding and knowledge of the Biblical languages does have a benefit! However, it does not mean that you must know Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek before you can start doing good Bible studies. Luckily a lot of people have gone before us and have done some great work to make things easier for us.

When doing word study it is also good to have some understanding of languages and language developments. Languages are put into language families to indicate that these languages share some common traits. This could include vocabulary, grammar and alphabet. In our study of the Bible we will deal with at least two completely different language families. We will deal with the Semitic family that include languages like Hebrew, Aramaic, Akkadian and Arabic. On the other hand we deal with Koine Greek which comes from the Hellenic grouping of languages within the Proto-Indo-European language family. This family also includes the groupings like Germanic and Celtic languages.  This simply means that when we study the words and the grammar of the languages, we need to be aware that we are dealing with two very different sets of rules for Greek and Hebrew/Aramaic.

When doing word study it is also good to have some understanding of languages and language developments. Languages are put into language families to indicate that these languages share some common traits. This could include vocabulary, grammar and alphabet. In our study of the Bible we will deal with at least two completely different language families. We will deal with the Semitic family that include languages like Hebrew, Aramaic, Akkadian and Arabic. On the other hand we deal with Koine Greek which comes from the Hellenic grouping of languages within the Proto-Indo-European language family. This family also includes the groupings like Germanic and Celtic languages.  This simply means that when we study the words and the grammar of the languages, we need to be aware that we are dealing with two very different sets of rules for Greek and Hebrew/Aramaic.

It is also important to remember that languages do not remain static. Languages change with time and the meaning of words can also change over time. The Scriptures we have today were written over an extended period of time, thus we always need to keep the time factor in mind when trying to determine the meaning of a word. This is not only valid for the vocabulary but also the alphabet being used. Hebrew specifically, has gone through several changes of their character sets. This is one of the techniques that is being used to date a manuscript, the shape of the characters being used. The written language also changed dramatically when the Masoretic scribes standardized the text and started added vowel pointings and other marks to the scrolls they were copying.

In the same way the Greek language has also changed. Very few people know that Greek was originally also written from right to left, as Hebrew is still written. Greek writing then changed to be written from both sides alternating (first line – right to left, second line – left to right, third line – right to left, etc…) and at the end it ended up being written left to right, as we write in English today. This was a very practical change as people moved from cutting letters out of stone or printing into clay tablets to writing with ink (that needed to dry). If a right handed person tries to write right to left with ink, the ink will surely smudge as it has not time to dry before the hand passes over it. Left to right allows the ink time to dry before the next sentence is written.

The tools we could use

When we want to do word study, we need to make sure that we have the right tools. As I stated before, the first “tool†you need is the Ruach to lead you. Over and above this, I could also recommend a couple of other tools that would make the process a easier. Here I will not necessarily point to products but rather specific tools. The choice of product will still be a personal choice. Exactly which products you use will be a factor of your budget and the frequency at which you will use these tools. A lot of these tools can be found free of charge on the Internet and at the same time you could spend thousands of dollars on professional quality tools. I am not stating that anyone of these two extremes is correct, it will have to be a personal choice. Personally, like most people, I started off by only using the free tools that are available. In the mean time I have made the transition to some more “professional†tools, and I can honestly say that I have seen the difference. But this is a completely separate discussion that is not within the scope of this study.

Reverse Interlinear Bible

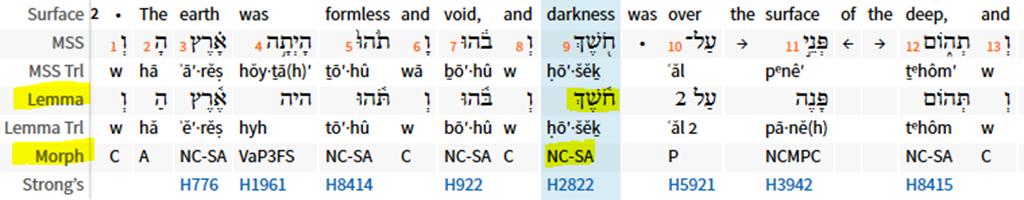

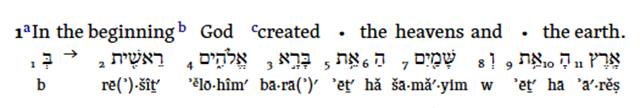

The most valuable tool that I have added to my toolbox for word studies is what is called a “reverse interlinear Bibleâ€. This is a version of the Bible that shows you the translated text (example – English) aligned with the original source text (Hebrew / Greek). This resource then allows you to see how the source text was translated to English. Most reverse interlinear Bibles also shows you a transliteration of the source language. Transliteration is the technique of writing the pronunciation of the original word in the sounds of the target language. In some cases they may even use phonetic spelling to indicate pronunciation.   Below is a sample of what Gen 1:1 looks like in a reverse interlinear Bible:

What you can also see from this text is a number next to the Hebrew words. As the reverse interlinear Bible is relating the Hebrew to the English text, we will of course loose the sequence of the original Hebrew sentence. These numbers next to the Hebrew words show us the original sequence of Hebrew words. In the first article in this series I explained about the different manuscripts that exist. It remains important that you know what manuscript was used for the translation of the Bible. This information is not really useful unless you already know Hebrew. Thus we may need some additional information to assist us in making more sense.

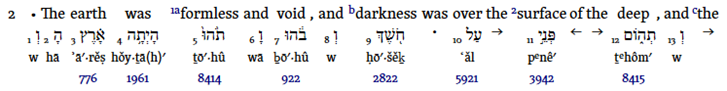

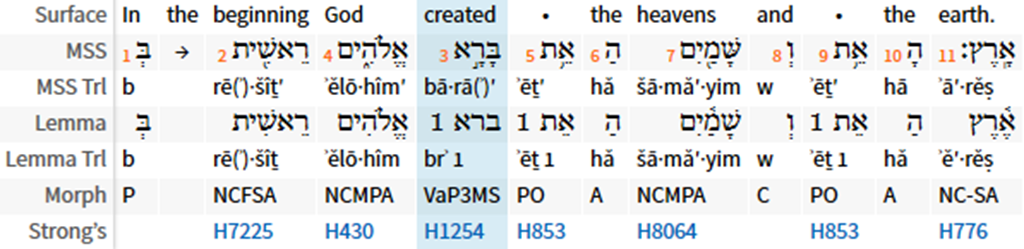

In order to simplify the transition between English and Hebrew/Greek, we have a number of systems that could aid us. The best known and most common is the numbering scheme introduced by James Strong around 1890. The Strong’s numbers is a scheme that assigns an unique number to each Hebrew and Greek word that appears in the King James Version of the Bible. A reverse interlinear Bible would also be able to show us this type of information. This will allow us access to a lot of other resources that will further explain this word. Below is Gen 1:2, coded with the Strong’s numbers.

If we use the Strong’s number, we can then look up a definition for the Hebrew word in Strong’s Dictionary and also see where else it was used in the KJV. Here is an example of one such entry for the word “darknessâ€:

The Strong’s Lexicon then provides us with this entry:

From these two entries we have learned the following:

- The Hebrew word for the word “darkness†in Genesis 1:2 is חשֶ×ךְ (chôshek)

- This word originates from the Strong’s word H2821 - חָשַ×ךְ châshak; a prim. root; to be dark (as withholding light);

- It is not always translated as “darknessâ€. It can have a literal and figurative meaning e.g. secret place, misery, death. From our study thus far, we would not be able to determine which one of the two to use here. Once again, get back to the context!

- It occurs 80 times in the Authorized Version of the Bible (aka the King James Version)

Unfortunately, this is the point where most people would finish their word study. Maybe some would do a Strong’s search and get all the scriptures that include this word. I strongly recommend that you move beyond this point in your word study to get the most impact and insight. As we continue, I will introduce you to more information that you could use.

Lexicons

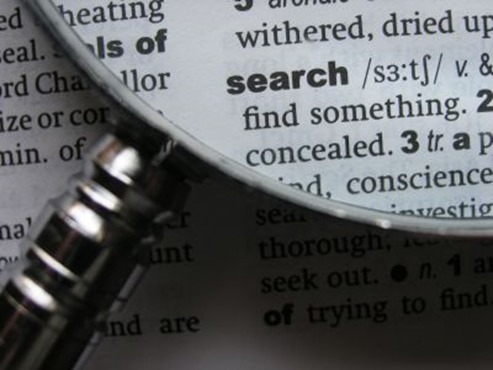

In the previous section you were already introduced to two more of our tools – lexicon and dictionary. I assume that all readers would understand what a dictionary is and how to use it. We would typically use an dictionary if we want to look up the exact meaning of an English word. Some dictionaries, like the Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary would also provide you with some background or history of the English word. Here is an example from this resource:

[Middle English derk, from Old English deorc; akin to Old High German tarchannen to hide] before 12th century

1     a : devoid or partially devoid of light : not receiving, reflecting, transmitting, or radiating light 〈a dark room〉

b : transmitting only a portion of light 〈dark glasses〉

2     a : wholly or partially black 〈dark clothing〉

b of a color : of low or very low lightness

c : being less light in color than other substances of the same kind 〈dark rum〉

3     a : arising from or showing evil traits or desires : EVIL 〈the dark powers that lead to war〉

b : DISMAL, GLOOMY 〈had a dark view of the future〉

c : lacking knowledge or culture : UNENLIGHTENED 〈a dark period in history〉

d : relating to grim or depressing circumstances 〈dark humor〉

4Â Â Â Â Â a : not clear to the understanding

b : not known or explored because of remoteness 〈the darkest reaches of the continent〉

5Â Â Â Â Â : not fair in complexion : SWARTHY

6     : SECRET 〈kept his plans dark〉

7     : possessing depth and richness 〈a dark voice〉

8     : closed to the public 〈the theater is dark in the summer〉 synonym see OBSCURE — dark•ish \ˈdär-kish\ adjective — dark•ly adverb — dark•ness noun 3

What is the difference between a lexicon and a dictionary? A lexicon is a specialized foreign language dictionary that limits itself to a specific body of knowledge, e.g. the Bible. Thus, a lexicon would be a dictionary that includes all the Greek and/or Hebrew words contained in the Bible. In contrast, a Greek dictionary could include words that were used during the same period of time in different literature e.g. the writings of Plato and Socrates. In lexicons the only challenge we have is that it is indexed according to the original Hebrew or Greek words. For those of us that do not know Greek and Hebrew, the numbering schemes, like Strong’s scheme, makes it much easier to lookup a word without knowing Greek or Hebrew.

Also, not all lexicons are created equal. We a have different types of lexicons that we use for different purposes. Let me discuss some of the more common lexicons that can be used. The most common lexicon that almost everybody has an electronic copy of is the Strong’s Lexicon. It is copyright free (it was compiled originally around 1890) and is therefor included in almost every Bible study software package that is available. It provides the following:

- A basic definition of the word in English. It may have one or more different definitions for each Hebrew/Greek word.

- In the paper copy it also supplies a complete list of all the verse in the Bible where this word is being used (concordance). Most software packages do not include this, as it is normally supported via a search function on the Strong’s number.

The basic definition of the word was determined by James Strong and his students when he compiled the lexicon originally. This is exactly the limitation of a lexicon like Strong’s. If it is out of copyright, that also implies that nobody is maintaining or updating the lexicon with what has been discovered or understood about the manuscripts or source languages since it’s last publication date. Since 1890 we have made lots of new discoveries (like the Dead Sea Scrolls) that have expanded or changed our knowledge of the source languages of the Bible. If you use a lexicon like the copyright free version of Strong’s you are still stuck in the 1890’s with your understanding of biblical languages. Another lexicon that is also used very often, the Brown-Driver-Briggs (BDB), includes the same type of information and was compiled in 1906. Most versions you will find today will also include references to the Strong’s numbers. Below is the BDB entry for the Strong’s H2822 (“darkness†in Gen 1:2) that we used earlier:

2. = secret place(s) Id 45:3 Jb 12:22 (|| צלמות); = hiding-place Jb 34:22 (|| id.), cf. ψ 139:11, 12;—on Ez 8:12, v. supr.

3. fig., a. = distress Is 5:30; 9:1; 29:18 (fig. of blindness), 42:7; 49:9; 58:10; 59:9; 60:2 La 3:2 Mi 7:8 ψ 18:29 = 2 S 22:29, Jb 15:22, 23, 30; 20:26; 22:11; 23:17; 29:3 ψ 107:10, 14 (in both || צלמות), 112:4 Ec 5:16; 11:8.

b. = dread, terror, symbol. of judgment Am 5:18, 20 Zp 1:15 Na 1:8 Ez 32:8 Jo 2:4; 3:4.

c. = mourning Is 47:5.

d. = perplexity Jb 5:14; 12:25; 19:8; confusion ψ 35:6.

e. = ignorance Jb 37:19 Ec 2:14.

f. = evil, sin Is 5:20() Pr 2:13.

g. = obscurity Ec 6:4(). 4

For Greek word studies we would typically find people also using Thayer’s “A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testamentâ€. This lexicon was published in 1889.

In this same category of lexicons, we also find lexicons that are more up to date and in most cases are still being maintained by their respective publishers. Due to this fact, these are  not available for free. They would require you to buy either a hardcopy book or electronic version that could be included in your Bible study software.

not available for free. They would require you to buy either a hardcopy book or electronic version that could be included in your Bible study software.

- Dictionary of Biblical Languages With Semantic Domains : Hebrew (Old Testament) (aka DBL Hebrew)

- The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (aka HALOT)

- A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (aka DBAG)

If it is within your means, I would strongly recommend that you invest in some of these resources to keep your word studies up to date with the latest academic findings on the Biblical languages.

We also have another group of lexicons that do not provide us with a list of potential meanings and places where words are used, but rather provide us with a discussion of the word. These lexicons would be more of a theological discussion of what the word means in the Biblical context, how it was used by different authors of the Bible and even some academic positions or discussions of the concept. These lexicons act more like a commentary on the word that is being discussed. The better known instance of this type of lexicon is most likely the “Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Wordsâ€. Another very common resource is “The Theological Wordbook of the Old Testamentâ€. Below is a small excerpt from a fairly lengthy discussion of the use of the term “darknessâ€Â in the Tanakh.

Genesis 1:2 uses ḥÅÅ¡ek referring to the primeval “darkness†which covered the world. In verse 4 the celestial luminaries divided the “darkness†from the light (cf. v. 18). And in verse 5 the “darkness†was called “night.†Elsewhere ḥÅÅ¡ek is equal or parallel to “night,†as in Josh 2:5; Job 17:12; 24:16; and Ps 104:20.

This word is used for the plague of “darkness†on the Egyptians (Ex 10:21–22; Ps 105:28). It also accompanied God’s appearance on Mt. Sinai (Ex 14:20; Deut 4:11; 5:23). 5

As you can see, this lexicon goes beyond the basic linguistic discussion of the word. In these type of lexicons, we already find the theology of the authors(s) coming into the text. Thus – a word of caution – read these lexicons with the understanding that it contains theology that has to be understood and verified. Do not simply accept their interpretation without reading the scriptures yourself.

We also have very specialized lexicons that focus on one specific topic in the Bible, or that takes a different approach. A lexicon that takes a very specific focus, is for example a lexicon of biblical names. Examples of this type of lexicon are “Hitchcock’s Bible Names Dictionary†or “The Exhaustive Dictionary of Bible Names.†These resources provide more details on the meaning names of people in the Bible. It is always insightful to also understand exactly what the name of the person means. In many cases, we learn much from a person’s calling by simply looking at the meaning of their name. Here is an example of such an entry:

Aaron (a’-ur-un) = Light; a shining light; a mountain of strength; enlightened; very high; to be high. Teaching; to shine. Chaldean: To be high. 6

Another very specialized resource that falls within this category, is the resource that allows us to move between Hebrew and Greek. We use this when we do a word study that crosses between the Tanakh and the Apostolic scriptures. When we do a search, we cannot use the English word as the bridge between the Hebrew and the Greek. The reason for that is that this is actually a many to many relationship. One Hebrew word can be translated into many Greek words and any Greek word could also describe many Hebrew words, once again: depending on the context. Thus, we get stuck with the challenge of what Greek word represents a chosen Hebrew word or concept in the specific context. Our best method is to use the Septuagint as the bridge. The Septuagint is a Greek translation of the Tanakh that was done around 200 years B.C. This translation was done by Alexandrian Jews. This means that their mother tongue was most likely Greek, but they had been studying the Hebrew scriptures their whole lives. The translation into Greek was not done by one person, but by a group of translators. The story behind the Septuagint claims that there were 70 translators and it took them close to 60 days to do the translation. Thus, the shorthand that is being used as well – LXX – 70 in Roman numerals. If we use the Septuagint we can chose a specific verse and word to see what the word is in the Hebrew text and compare this with the Greek Word in the Septuagint. Going the other directions is however a bit more difficult. If I want to look up which Hebrew words are used to translate a specific Greek word, then the search becomes a bit more difficult. Now we need a lexicon that gives us a specific Greek word and then highlights all the Hebrew words that was translated with this Greek word in the Septuagint. This is a very specialized resource and is not that easily available in software packages. An example of this in book form would be Hatch & Redpath’s A Concordance to the Septuagint: And the Other Greek Versions of the Old Testament (Including the Apocryphal Books) (Greek Edition) published by Baker Academic. This is not a cheap resource but it is very unique. It is really the only reliable way to be able to move between the Tanakh and the Apostolic Scriptures.

Now that you have been introduced to all these wonderful resources, I would like to ask a very thought provoking question: With all the capabilities of the Bible study software on the market today, do we really still need to use lexicons? What took James Strong and his team of 100 students a couple of years to do is now at my fingertips. I can search for any Hebrew word in my reverse interlinear Bible within seconds. I can get a complete list of all the verses that use it and also get a good grammatical analyses of these words.

Finding the original word and then doing basic word lookup is really a first step to the next stage in your Bible study (after merely reading the Bible translation). Unfortunately, this is also the place where quite a large number of people get stuck. They do not proceed to the next level of detail that I will now show you. It is at this next stage is where the real study and thinking start to happen. This is where the real fun starts.

More methods to study the word

Unfortunately you are going to have to do some work to enjoy the benefits of this next stage. The biggest amount of work you will do is to dust off a lot of stuff you were taught at school. For some people, including myself, that may be a couple of years back! In order to do proper word study we need to understand the theory of what we are working with. The basics of this was taught to you as part of grammar. I know, we all simply loved studying all the grammar rules at school! Now is the time you will get an answer to the question every child at school asks – “When will I ever use that?â€

Understand the grammar

Although I will keep on referring to “words†as the basic building blocks of what we are doing here, please do remember that a word could also be part of a phrase. Then it would not really make sense to study the word in isolation. It then becomes more important to understand the contextual significance of the phrase. Watch out for these!

I need to take you back to grammar school, because one of the first things we need to identify when doing this level of word study, is the category/class of word that we are using. For those that do not recall, here are some word categories:

- Verbs

- Nouns

- Adjectives

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Adverbs

It is important to know exactly what these mean, as they become a building block for a number of things we would refer to from now on. The process of what we are starting to do here is identify the morphology of the word. What does this mean:

In basic terms this means that we add things to the front and/or back of the basic words to give them specific contextual meaning. For example, for verbs we could post or prefix a word to show tense (past, present or future tense: “walk†could become “walksâ€, “walking†or “walked†) and for a noun in English we normally postfix to indicate a plural (“tree†becomes “ treesâ€). We also change a pronoun in English to show a gender for example: I, he, she or it. This basic word that I am referring to, is also referred to as the “Lemmaâ€. To make it very simple, the lemma of a word is that form of the word that you would typically look up in a dictionary. You would look up “ treeâ€Â and “walk†– to continue my two examples. Thus, the lemma of “walking†would be “walk†and the lemma of “trees†would be “tree.â€

I am simplifying here by using English examples, but what we really need to get to at the end, is the ability to understand the complete morphology of the original biblical languages. This, however, is not something you would do overnight. Give yourself a couple of years just to get to basic proficiency with Hebrew and Greek. We have again been saved from all the hard work by a couple of people who have put their knowledge of these languages into resources that could make our lives a lot simpler. We can now extend the earlier examples of what I showed you from the reverse interlinear Bible, by also adding the morphological analysis of each word.

We now see a line of codes added just above the Strong’s number for each word. These provide a short code for the exact morphology of each word. We see another two lines that show us the lemma of each word (as well as the transliteration of the lemma). For example, we see that the word “darkness†in this context, is a common noun in the singular format. As this is a common noun in the singular form, we would expect that it is also the lemma. If I now do a search of the NASB on the lemma, I get a result of 80 occurrences in 77 verses (same as what we saw with the Strong’s references). But if I now narrow my search to the complete morphology of the word, I get only 77 occurrences in 74 verses. Now we have an interesting study to do – why are the 3 instances different? Are they in the plural? Can darkness be plural? I will leave this for you to go and figure out.

If we get to understand this level of detail we can start to discover really interesting information. When we now do a word study and we know that the word we are studying is a verb, then we can start to ask interpretative questions about the word. This will tell us a lot more than what the average lexicon would do. For verbs we could try and answer the following questions during our study:

- What kind of verb action does the context suggest? (in process, repetitive, completed or intermittent?)

- Who or what is performing the action? (can anybody do it or only a specific person/thing or group?)

- To whom or what is the action being performed?

- What is the verb producing or causing?

- Are there other verbs/actions that produce the same thing?

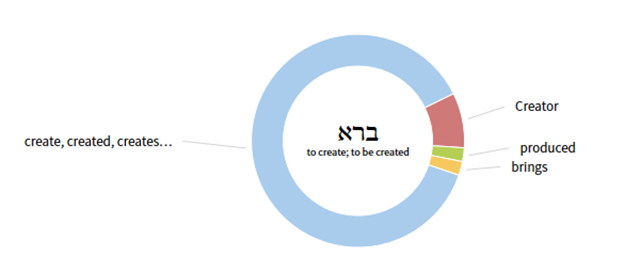

Let us look at a very simply example of the verb “createâ€. In Genesis 1:1 we see this Hebrew word is “bara†– Strong’s H1254.

Let us for example try to answer the question – “who can create?†To answer this question, we need a bit more detailed word study. We will start by doing a lemma search on “baraâ€. From this we see that the word is not always translated as “createdâ€.

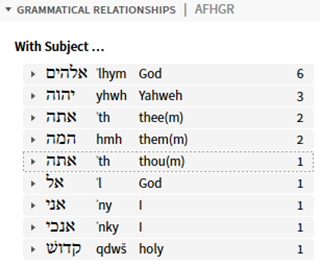

The next question would now be – who performs this action? Using the software tool to do the grammatical analysis for me, I get the following result:

We see that at least 10 of the occurrences it is clear that it is YHVH that creates. By looking at the specific verses for the other subjects, we can also see that it is actually referring to YHVH. Here is an example of what the drill-down would look like:

From this sentence, we can see that the Hebrew word “bara†is used when YHVH is creating. This would now lead to the next question: “Can only YHVH create or is there another verb that could also indicate the action of creation?†If we search the NASB for the English word “create†in the Tanakh, you will find the 42 occurrences always leading you to the Strong’s number H1254 (bara). From this we can see that in the Biblical text only YHVH can “baraâ€! If we now start looking for synonyms like “makeâ€, “buildâ€, “generate†or “produce†we could look at who else can perform similar actions. We find H6913 (Ê¿Ä·śÄ(h)), H7919 (śķḵǎl) and H3772 (kÄ·rǎṯ) all being used as the Hebrew word translated to “make†in the Tanakh. In these cases it is not only YHVH that makes, but also man. Thus we can conclude that the Hebrew word “bara†has a very specific use in the Tanakh. For further study: What is unique about the action “bara?â€

When we study a noun, we also need to start asking specific questions. However, the questions for a noun would be different than for a verb. Here are some examples of the questions that you could ask about a noun?

- What form can the noun take – person, place or object?

- Can it be singular and plural?

- What actions can this noun perform i.e what can they do?

- What actions can be performed on this noun i.e. what can happen to them/it?

Two interesting words to go an test this on would be H4397 (malak) that is translated “messenger†or “angel†and H8085 (Å¡Ä·mÇŽÊ¿) that is translated as “witnessâ€.

Historical Development of words

When we look at the meaning of a specific word, it is good to also keep in mind who it is that is using the word and the time period in which the translation was done. What we read and what was written, does not always mean the same thing.

Let us look at another example to see how the historical meaning of a word could put us on a wrong track. Please look at this verse:

Matthew 5:48

48 “Therefore you are to be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.

What is the message that Y’Shua is trying to get across? Are we to be perfect? What exactly did Y’Shua mean with “perfect� Does this mean without any flaw? Is it realistic to think that we will ever be as “perfect†as YHVH? Let us see how Strong’s defined this Greek word originally in 1890.

1 brought to its end, finished.

2 wanting nothing necessary to completeness.

3 perfect.

4 that which is perfect.

4A consummate human integrity and virtue.

Let us now get a more modern (last updated in 1997) understanding of this word:

1. LN 88.36 (morally) perfect (Mt 5:48; Jas 3:2), for another interp, see below;

2. LN 73.6 genuine, being true (1Jn 4:18);

3. LN 79.129 (physically) perfect (Heb 9:11);

4. LN 68.23 complete, finished (Jas 1:4);

5. LN 88.100 mature in one’s behavior (Eph 4:13; Mt 5:48), for another interp, see above;

6. LN 9.10 adult (Heb 5:14);

7. LN 11.18 initiated, one inducted into the believing community (Php 3:15; Col 1:28) 8

Here is an extract from another modern (last updated in 2000) lexicon:

1. pert. to meeting the highest standard

2. pert. to being mature, full-grown, mature, adult

3. pert. to being a cult initiate, initiated.

4. pert. to being fully developed in a moral sense 11

Could some of the more modern understandings like “complete†maybe be a better rendering of the original Greek term? From these different definitions it is clear that our understanding of the original Greek word has expanded quite a bit over time.

This is also one of the reasons that I recommended in the first article that you use a fairly recent translation. We know that English words have also changed their meaning over time. Words used in the original King James version, simply do not mean the same any more. Due to the fact that we do not know the English from this time, we will interpret these words with their modern meaning. This could lead to error in a number of cases. here is a very simple example for you:

‎1 Co 16:15 (KJV 1900)

I beseech you, brethren, (ye know the house of Stephanas, that it is the firstfruits of Achaia, and that they have addicted themselves to the ministry of the saints,)

Based on our modern English, what do you think of when you read the word “addicted� Is this a positive or negative thing? Let us now see how a modern translation interprets this word:

1 Corinthians 16:15 (NASB)

15 Now I urge you, brethren (you know the household of Stephanas, that they were the first fruits of Achaia, and that they have devoted themselves for ministry to the saints),

Seriously, would you ever have associated it with the modern English word of “devoted?â€

Things to watch out for

In order for us to perform sound studies and make reliable conclusions from our word studies, I would also like to point towards some typical mistakes that are made. These mistakes are made in most cases simply because the student does not understand the basics of how languages work. In order to explain these typical mistakes, I will mainly use English words to explain the principles. I know that English does not always work the same as Hebrew or Greek, but in this case the English is good to simply illustrate the point.

Common Roots

The first mistake that is made comes from the basic assumption that words that share a common root have a common meaning. Although this sounds very possible, let us look at some English words that share the same three consonants. Do the words “baldâ€, “buildâ€, “bold†or “boiled†have a common meaning that you could find? All these words use the same three consonants as their base “bld.†I think that you will agree with me that in this case it does not appear to have a common thread.

Let us look at a Hebrew example – the three letters עיר could mean:

- city, town or village – עִיר (ʿîr)

- anguish / anxiety – עִיר (ʿîr)

- a male donkey – עַיִר (ʿǎ·yir)

You will need to get very creative to find the commonality between these three meanings.

Homographs

In this scenario we have the problem with a special type of word, called a homograph. A homograph is normally two or more words with the exact same spelling, but completely different meanings. When somebody shouts the word “duck†what would you do? You can either get out of the way fast or you can start looking around for some type of a water bird. In English the word “duck†is a homograph. To give you some more examples of English homographs:

- bass: are you talking about some aspect of music or a type of fish?

- bank: are going to a financial institution or the side of the river?

- wound: have you been injured or have you tied something up?

As you can see from these examples that I have provided, there does not necessarily have to been a connection between two homographs. Thus the rule that we must make here is that you cannot assume a meaningful relationship between homographs. The only way to clearly understand the meaning of the word is to look at the context.

Let us find an example in the Hebrew:

The Hebrew word “hÄ·lÇŽl†can have three different meanings depending on the context. If we look this word (H1984) up in the Dictionary for Biblical languages (DBL), we will actually find three separate entries:

2145 I. הָלַל (hÄ·lÇŽl): v.; ≡ Str 1984; TWOT 499, 500—LN 14.36–14.52 (hif) shine flash, radiate, i.e., have bright or clear light be visible from a source (Job 29:3; 31:26; 41:10[EB 18]; Isa 13:10+)

2146 II. הָלַל (hÄ·lÇŽl): v.; ≡ Str 1984; TWOT 499—1. LN 33.354–33.364 (piel) praise, cheer, brag on, extol, i.e., extol the greatness or excellence of a person, object, or event; (pual) be praised, be worthy of praise (2Sa 22:4; 1Ch 16:25; Ps 18:4; 48:2; 78:63; 96:4; 113:3; 145:3; Pr 12:8; Eze 26:17+), note: also verbal song and singing with the same themes; (hitp) boast in, praise, glory in, i.e., express words of excellence, with a focus on the confidence one has in the object, person, or event (1Ch 16:10; Ps 34:3[EB 2]; 52:3[EB 1]; 63:12[EB 11]; 64:11[EB 10]; 105:3; 106:5; Pr 31:30; Isa 41:16; 45:25; Jer 4:2+), see also domain LN 33.109–33.116; 2. LN 33.368–33.373 (piel) boast, brag, formally, praise about, i.e., speak words which show confidence in an object, which is not deity (Ps 10:3; 53:3[EB 1]); (hitp) boast, brag (1Ki 20:11; Ps 49:7[EB 6]; 97:7; Pr 20:14; 25:14; 27:1; Jer 9:22[EB 23],23[EB 24]; 49:4+), note: in some contexts this can be improper confidence, so be haughty, see also domain LN 88.206–88.222; note: see also 2149

2147 III. הָלַל (hÄ·lÇŽl): v.; ≡ Str 1984; TWOT 499—1. LN 88.206–88.222 (qal) be arrogant, boast, i.e., be in a state of improper pride and haughtiness (Ps 5:6[EB 5]; 73:3; 75:5[EB 4]+); 2. LN 32.42–32.61 (poel) make a fool of, i.e., turn another into one who has no capacity for understanding, implying a condition which can be ridiculed (Job 12:17; Ecc 7:7; Isa 44:25+); (poal) be foolish (Ecc 2:2+), for another parsing, see also 4538.5; 3. LN 33.387–33.403 (poal) mock, slander, rail against, i.e., speak harmful words against another, implying a lack of respect (Ps 102:9[EB 8]+); 4. LN 30.1–30.38 (hitpoel) mad, insane, i.e., to think in an irrational manner and so behave in kind (1Sa 21:14[EB 13]; Jer 25:16; 50:38; 51:7+); 5. LN 42.7–42.28 (hitpoel) furious, charging, i.e., to act. in a manner that performs with great energy and intensity, implying that the action may border on being unthoughtful or even reckless in manner (Jer 46:9; Na 2:5[EB 4]+), note: for MT text in Isa 52:5, see 3536 8

Here we see that this one word can mean:

- to shine

- to praise

- to be mad or insane

These three different meanings do not really have a clear common thread and only context will tell us which one of the three to choose. Later we will see a resource that could assist us in solving this problem.

that could assist us in solving this problem.

Joined words

Does the word “houseboat†have the same meaning as the two words that it was made up from, house and boat? Yes, in this case it will be something that floats on the water that you could live in. Can we now make the general rule that a new word has the combined meaning of the words that make it up? This is something that I have seen many times in word studies. In some cases, like this example, it is true. However, we cannot generalize this rule. If we were to make this a general rule, how would you explain a butterfly?

Words that occur once only

Another very special situation also occurs every now and again. This is when we search a word that only occurs once in the Bible? How can we now make a general conclusion about how this word is to be interpreted?

These words are referred to as “Hapax legomenon†that simply means (in Greek) “said once onlyâ€. The scholars have tried several methods to understand these occurrences. Some of these include:

- Assume that the word is a scribal error and try to correct it by finding a word that looks similar that will fit in within the context

- Search for other writings of the same period to see if the word van be found in writings other than the Bible

- Look at languages from the same language family that is closely related to see if the word might have originated in another language

Today, we will tend to use the last two strategies more often. This is also the reason why people involved in Bible translation, often do not only study the languages that the Bible text appear in, but also the related languages like Akkadian and Arabic. Specifically Greek scholars will also spend a lot of time studying the Greek of non-Biblical text of the same period. In the case of Greek, we do have a very big collection of manuscripts that have survived from the same time period as the Apostolic scriptures. In this case a lexicon like “A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literatureâ€11 published by the University of Chicago Press, becomes very useful. it also includes the use of the Greek word in the writings of people like Philo, Josephus and the apostolic fathers. This widens the base a lot and reduces the number of singular use words.

A special type of lexicon

Now that I have explained all these typical problems the we experience when doing word Study, I want to make you aware of a another special lexicon that exists. Â It is not something that is easy to use, but once you understand the challenges that I have explained above, you will appreciate what this lexicon tries to achieve.

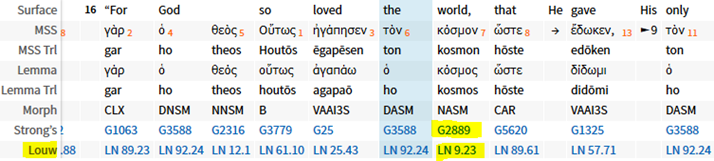

This lexicon was created by Johannes P. Louw and Eugene A. Nida. Both these two men spent their lives working on better ways to do Bible translations. This lexicon is called “ The Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains†also known as the Louw-Nida. It is being published by the United Bible Societies and is currently in it’s second edition published in 1996. The lexicon is only available in print form or from one of the major Bible software companies. What is different about this lexicon compared to the others I have discussed so far, is that this lexicon introduces the concept of semantic domains (word groups). Thus, in this lexicon the Greek vocabulary is not presented in an alphabetical order, but it is classified into 93 semantic domains. Different meanings of the same lexical unit (word or idiom) are defined in the respective domain. This means that the same word may appear multiple times in this lexicon, but will then be classified in a separate semantic domain. You can use this link to see a list of the semantic domains. How does this help us? Let me explain by using a good example. Study these two verses:

John 3:16

16 “For YHVH so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life.1 John 2:15

15 Do not love the world nor the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him.

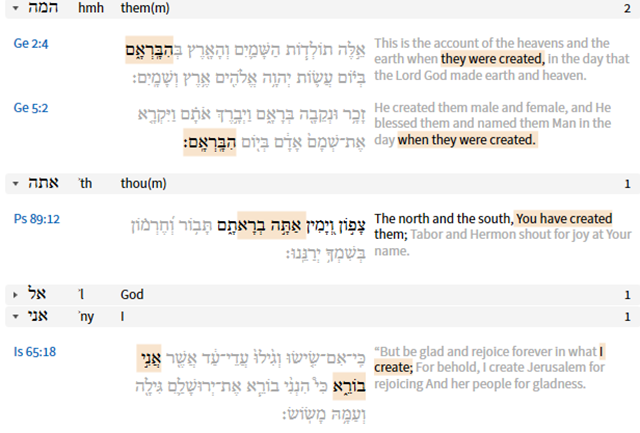

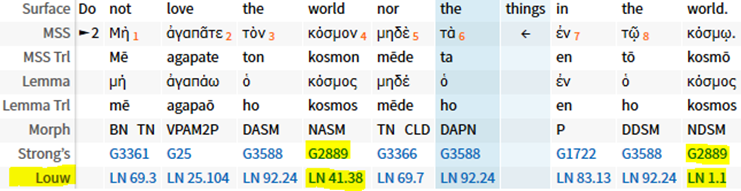

Do you spot the apparent contradiction in what the apostle John is writing in two of his writings? He is telling us that YHVH loved the world, but that we should not, because then we are not following YHVH. What makes this worse now is that the Greek word used for “world†is in both cases “κόσμος†G2889 that is transliterated as “kosmosâ€. So if it is the same noun (G2889) with the same verb “love†(G25) we must not do what YHVH does? Now let us see how Louw & Nida helps us to solve this problem. Once again, we will see – it is about the context!

Louw-Nida introduced a new numbering scheme in their lexicon that is comprised of two parts. The first part is a number that points to the semantic domain and the second points to the word entry within the domain. Below are screenshots that now also add the Louw-Nida numbers to the reverse interlinear Bible entries of these two verses. Take note of the Strong’s and Louw-Nida entries for the word “worldâ€.

Thus, one of the Louw-Nida numbers for kosmos (G2889) would be LN 9.23. Semantic Domain 9 is about Human Beings. This is the instance of the word that is being used in John 3:16. The other entry being used in 1 John 2:15 is LN 41.38 where domain 41 deals specifically with words related to “Behavior and related states.† Let us look at what this looks like in the lexicon entries. We will start with a Strong’s entry for the word and then the two Louw-Nida entries.

The Strong’s Entry

1 an apt and harmonious arrangement or constitution, order, government.

2 ornament, decoration, adornment, i.e. the arrangement of the stars, ‘the heavenly hosts’, as the ornament of the heavens. 1 Pet. 3:3.

3 the world, the universe.

4 the circle of the earth, the earth.

5 the inhabitants of the earth, men, the human race.

6 the ungodly multitude; the whole mass of men alienated from God, and therefore hostile to the cause of Christ.

7 world affairs, the aggregate of things earthly.

7A the whole circle of earthly goods, endowments riches, advantages, pleasures, etc, which although hollow and frail and fleeting, stir desire, seduce from God and are obstacles to the cause of Christ.

The Louw-Nida Entries

1.1 κόσμοςa, ου m: the universe as an ordered structure—‘cosmos, universe.’ ὠθεὸς ὠποιήσας τὸν κόσμον καὶ πάντα Ï„á½° á¼Î½ αá½Ï„á¿· ‘God who made the universe and everything in it’ Ac 17:24. In many languages there is no specific term for the universe. The closest equivalent may simply be ‘all that exists.’ In other instances one may use a phrase such as ‘the world and all that is above it’ or ‘the sky and the earth.’ The concept of the totality of the universe may be expressed in some languages only as ‘everything that is on the earth and in the sky.’ 10

9.23 κόσμοςd, ου m: (a figurative extension of meaning of κόσμοςa ‘cosmos, universe,’ 1.1) people associated with a world system and estranged from God—‘people of the world.’ οá½Îº οἴδατε ὅτι οἱ ἅγιοι τὸν κόσμον κÏινοῦσιν ‘don’t you know that God’s people will judge the people of the world’ 1 Cor 6:2. 10

41.38 κόσμοςc, ου m; αἰώνc, ῶνος m: the system of practices and standards associated with secular society (that is, without reference to any demands or requirements of God)—‘world system, world’s standards, world.’

κόσμοςc: δἰ οὗ á¼Î¼Î¿á½¶ κόσμος á¼ÏƒÏ„αÏÏωται κἀγὼ κόσμῳ ‘because of whom the world is crucified to me, and I to the world’ Ga 6:14. It may be particularly difficult to speak of the world being crucified, and therefore in a number of languages one must employ a somewhat fuller restructuring, for example, ‘because of Christ, the way in which people in this world live is as though it were dead as far as I am concerned, and I am dead, so to speak, as far as the way in which people in this world live.’

αἰώνc: εἴ τις δοκεῖ σοφὸς εἶναι á¼Î½ ὑμῖν á¼Î½ Ï„á¿· αἰῶνι τοÏτῳ, μωÏὸς γενÎσθω ‘if anyone among you thinks that he is a wise man by this world’s standards, he should become a fool’ 1 Cor 3:18. αἰών in 1 Cor 3:18 may also be rendered as ‘by the way in which people in this world think’ or ‘by the things which people in this world think are right.’ In Mk 4:19 the phrase αἱ μÎÏιμναι τοῦ αἰῶνος may be rendered as ‘the cares which people in this world have’ or ‘the way in which people in this world worry about things.’ 10

We find that the Strong’s entry contains 10 different definitions for the same Greek word. These definitions do overlap with different entries in the Louw-Nida scheme, but in the Louw-Nida scheme, these are separate entries. This gives us a bit more guidance as to which form of the word to use when. Remember – Louw & Nida were also people like you and me. They brought their theology with them and also could have made mistakes. This means that we should not take their view as absolute, but rather as a guidance and an aid. It does help us solve a bit more of the problems we encountered above.

Conclusion

During this study, I hope to have explained some of the useful things that I have learned over the last couple of years. Please remember that this series of articles was never intended to be a complete course on Biblical interpretation, but simply some pointers to help you get you going towards the next level of Bible study. If you get to the point where you understand all that I have tried to explain in these four articles and you are now in the position where you apply these techniques consistently, you have not yet reached the end. There are some more advanced topics like sentence diagrams, logical reasoning and even more advanced literary devices that you could get to know and appreciate. Of course, there is always still the Biblical languages to keep you occupied. Most language students will confirm that learning a Biblical language is a task that could keep you occupied for several years.

Last remark, please make sure that your Bible studies do not become pure academic exercises. These studies should always be done in the context of your relationship with your Creator and Savior. Nothing replaces your personal relationship. These studies should only help you to improve that relationship, never substitute it. This frantic search for knowledge have led many astray in the past. Please ensure that you keep the priorities in check. Wishing you many happy hours of getting to know you Creator and Savior via His Word.

Continue reading -Â Who are the Samaritans? – An example of an contextual study.

References

- Strong, J. (1996). The New Strong’s Dictionary of Hebrew and Greek Words. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

- Strong, J. (2001). Enhanced Strong’s Lexicon. Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software.

- Merriam-Webster, I. (2003). Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary. (Eleventh ed.). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- Brown, F., Driver, S. R., & Briggs, C. A. (2000). Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (electronic ed.) (364–365). Oak Harbor, WA: Logos Research Systems.

- Alden, R. (1999). 769 חָשַ×ך. In R. L. Harris, G. L. Archer, Jr. & B. K. Waltke (Eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (R. L. Harris, G. L. Archer, Jr. & B. K. Waltke, Ed.) (electronic ed.) (331). Chicago: Moody Press.

- Smith, S., & Cornwall, J. (1998). The exhaustive dictionary of Bible names (1). North Brunswick, NJ: Bridge-Logos.

- Van der Merwe, C., Naudé, J., Kroeze, J., Van der Merwe, C., Naudé, J., & Kroeze, J. (1999). A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar (electronic ed.) (51). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Swanson, J. (1997). Dictionary of Biblical Languages with Semantic Domains : Hebrew (Old Testament) (electronic ed.). Oak Harbor: Logos Research Systems, Inc.

- Strong, J. (2001). Enhanced Strong’s Lexicon. Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software.

- Louw, J. P., & Nida, E. A. (1996). Vol. 1: Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament: Based on semantic domains (electronic ed. of the 2nd edition.) (106). New York: United Bible Societies.

- Arndt, W., Danker, F. W., & Bauer, W. (2000). A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature (3rd ed.) (995–996). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Leave a Reply